Stolz

Visa Recipients

- STOLZ, Charles P A T

Age 17 | Visa unnumbered - STOLZ, Edith P

Age 10 - STOLZ, Emil (Buby) P

Age 21 - STOLZ, Henri P

Age 43 - STOLZ, Isidore P

Age 14 - STOLZ, Rosa née HAMMEL P

Age 44 - STOLZ, Sylvain P

Age 13

About the Family

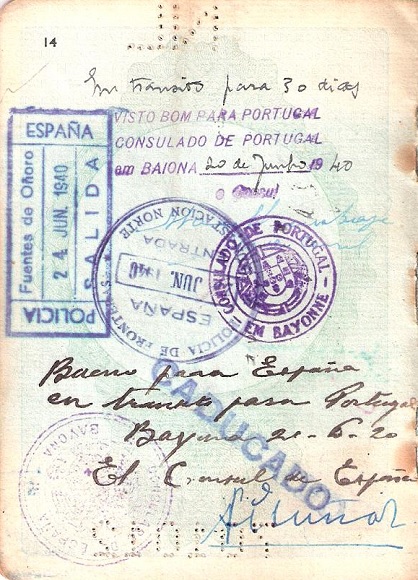

The STOLZ family received visas signed by Vice-Consul Manuel Vieira Braga following instructions from Aristides de Sousa Mendes in Bayonne, France on June 20, 1940.

The family crossed into Portugal where they lived in Coimbra and later Lisbon. They subsequently traveled to the Dutch East Indies.

- Photos

- Artifact

- Testimonial

Testimonial of Chaim GAON, born Charles STOLZ

From “The Grand Book of Brabosh memoirs – 200 Years of Jewish Presence in Flanders/Antwerp” by Sylvain Brachfeld. This chapter was written in May 1998.

I was born in 1922 in Borgerhout, Antwerp. My father, Henri Stolz, was born in Antwerp, but my grandfather David Stolz, came from Vienna at the age of 18. He was a Gabbai in one of the synagogues and was the only believer in our family. He was selling books and later he was a diamond worker. My father was born in 1899. He had several brothers: Bernard who was a medical doctor, Isi was selling rain coats, and Charles who is also a doctor and still lives and practices in New York. There were also two sisters: Marieke-Miriam who died, and Laura who married Yecheskel Wolf, and is the mother of Isi Wolf.

In 1914, when the Germans occupied Belgium, my father fled to Holland. In Scheveningen he met my mother Rosa Hammel who was also from Antwerp, and they got married and obtained Dutch nationality. The parents of my mother came from Jaroslaw, Poland. My grandfather Jacob Hammel had a job in furs. In 1922 my parents came back to Belgium. We lived on Antoon van Dijckstraat, and also my two grandmothers lived on the same street. My grandmother was a Gutwirth, a rich family in the diamond business.

My father was a very sociable man. He got along with everybody. He spoke many languages and was a very good salesman. Selling was in his blood. The Gutwirth firm sent my father to Indonesia, which was called back then the Dutch East Indies, to sell diamonds. I was only 6-months old when my mother left to Batavia (Jakarta, Indonesia) to join my father. I was raised by my grandmother until the age of 4 when my parents returned from Indonesia. My mother’s brothers had left at that time for Cologne in Germany to deal in furs.

In 1928 my father decided also to go to Cologne and became a textile merchant. Business was good. I attended the Jewish school in German, a language I knew because I had a German nanny (Fraulein). I was in Cologne for four years. My older brother went already to the “Gymnasium” (high school).

One day my father’s office was attacked by Nazi S.A. youth. Police brought him home while the Nazis followed them. We realized that the situation was really dangerous for us. We had at the time two Maybach (ultra-luxury German brand) cars with drivers and a good life. Shortly after that attack we collected our belongings and drove back to Antwerp where my father restarted his business. He had a replacement person in Cologne who took care of my father’s affairs and therefore was able to recover much of his money. That money was invested in the Antwerp Minerva car factory owned by Sylvain Salomon de Jong (a Jew of Dutch origin) and eventually got lost when the company went bankrupt.

We were at home with five kids: Emile who now lives in Australia, Isidore and Sylvain, who passed away, and my sister Edith who also lives in Australia. I went to a school at the Belgiëlei street. I had good tutors, very helpful. I learned Dutch very quickly. Later I went to the Royal Atheneum (high school) where we had a friendly gymnastics teacher whom we called “polar bear” and nicknamed him “horsehead”. Rabbi Shapira taught us Judaism classes. I have, though, bad memories of our history teacher who was pro-Nazi. Our director Declerk was not a kind man, but he was a great Belgian patriot.

In general I have good memories of the Atheneum school and I still remember the names of a few friends like Harry Wachsberg who lives in the US, Henri Teichler who is also in the US, Silberberg who changed his name to Randolf, and other names like Roisen, Ferman, Laub.

To my regret I have to say that the relations with the non-Jewish boys were not so good. At school itself it was all right most of the time and I had several friends among my classmates. One, named Verboven, was a close friend. He became later a politician. But on the streets things went badly. We lived on Helenalei Street so I had a long walk to the Atheneum.

Along the city park and in the streets there were groups of youngsters shouting at me “dirty Jew.” I could not stand that and it often resulted in fights. I was beaten and went to school with bruises and blood on my clothes. I then bought a knuckleduster and fought back. That went on for some time, but it was no solution. So we went in groups of five or six Jewish boys and then all was quiet, because most of the time we outnumbered them... But the memory of those “dirty Jew” shouts is still in my mind and left a very negative impression.

Another incident that is still on my mind happened when I was with my brothers at the beach, I think it was in Blankenberge. We dug a big hole in the sand when three boys came to destroy it all. They were bigger than us (I was about twelve at the time and my brothers were younger) but we defended ourselves. A man nearby separated us. Then one of the boys shouted “They are Jews!” and then the man returned immediately to his chair and gave a sign that he did not want to be involved. Now this was a “good man” who wanted peace between fighting children but because we were Jews it was “okay” to beat us. I also remember when one day I went to the cinema with my brothers and were beaten by children sitting behind us.

We lived for a while on Isabellalei Street in a house where the garden was bordering a building on Belgiëlei Street. In that building lived the Van Parys family, fruit merchants. I still remember the “LVP” sign on the oranges and bananas. They were a very rich Catholic family. With the Van Parys kids we were close friends. They came to us through the garden wall and we went to visit them. We played all kind of games including something about the Wall of Jerusalem. So I also had good experiences but nevertheless I can still hear those “dirty Jew” taunts.

We had a Jewish club called “Achduth.” I still remember the names of a few members like Lou Steinfeld, who later left for Rio de Janeiro, Henri Grauer who I believe is in the US, Theo Lewkowicz, and the girls Dora Steiner, Betty Gans, Tamara (whose last name I forgot), Dora Werzberg, who is still active in the US, and a few more friendly girls. Achduth was a Zionist organization with no affiliation to any political Zionist party. It had a library of 300 books and collected money for the Jewish National Fund to purchase land for the Jewish pioneers.

I will always remember that Friday, May 10th, 1940. I was preparing for my studies and school assignments and slept little that night. Suddenly I heard loud noises. I went to the window and saw aircrafts flying over town and a series of cigar-shaped bombs dropping down from the airplanes. This was war, after the drôle de guerre that had been going on for the last six months. But now it was no game anymore. Banks and the diamond bourse with its safes were closed. The family could not withdraw cash and left for the coast. After a few days, when civilians were not allowed to travel, my mother said it was time to leave.

We fled to France and arrived at Dunkirk, I think in fact behind the German tanks that had moved very fast ahead. Every time when German airplanes appeared over us, people ran to the fields and to the canals. The pilots aimed at the civilians, shooting all the time. I saw a pilot targeting a farmer and his two horses, shooting at him several times. It seemed the Germans wanted to create panic among the people. There were also soldiers in the crowds, including British, but because of the panic it was impossible for them to operate as an army.

We too were in that crowd and could hardly make any progress. There was no petrol, not even water. The French farmers behaved terribly. I saw a farmer standing next to a well holding up a glass of water while his wife sold it for twenty francs. His son stood next to him with a loaded shotgun to protect his parents. Near the road others were selling petrol in metal cans for inflated prices. My father thought to be clever and stuck his finger in to smell the can. After a few kilometers our car’s engine began to cough and it stopped. In the can my father bought, under a layer of petrol there was only water... So we lost our car all of a sudden and had to walk with the thousands of refugees. In the meantime the Germans continued to fly over us and shoot at the people.

We passed the village of Tréport. At one point we managed to steal somewhere a small carriage and put our old granny on top of it together with our luggage. We continued walking when suddenly nine aircrafts came towards us. I think they were Junkers. They dropped bombs that made a sharp whistling sound before exploding. There was a great panic. I jumped into a house whose glass windows were shattered. It was terrible. Women were praying along the roadside and there were casualties and dead people.

Finally we arrived at Rouen 123 km from Paris. The river Seine runs through the city and there is a bridge that stands on a central pillar. There were hundreds of people there and you could not move ahead. In a few minutes German planes came again, everybody ran in all directions. At that moment the bridge closed up. On the bridge there was a railway and some wagons. I crawled under one of them. Next to me was a French boy of about twenty. I was seventeen. He said to me caches-toi (“hide”). Two Stuka (Junkers) planes were aiming and shooting at the boats on the river. The French boy took his rifle and put a bullet in the barrel. It fell on the ground. He picked it up, cleaned it with his sleeve, took the gun again and shot at the airplanes. They repeated their attacks and fired at the wagons. I could see the pilot. When they left one of the ships was burning with huge clouds of smoke. The Frenchman and I embraced each other. We survived!

I went looking for my family who had disappeared. The bridge was blocked. I was told that if I go back 10km I would find a pedestrian bridge and from there I could walk back along the other side of the river to get to Rouen train station. There was no other way, so I started to walk. After a few kilometers I found my family who followed the same route. We were happy to be together again. After a long walk we arrived at the station where thousands tried to find a place on the train to Paris. There was little chance to get on that train. You couldn’t go with any luggage because there was room only for people who were trying to save their own lives.

There we were standing with our grandmother who was in her seventies (which was considered an old woman at that time), and a small child (my sister). When the train arrived, we tried to push ourselves with the others into the train. Suddenly someone shouted laissez-passer la grandmère (“let the grandmother pass”) and all of a sudden people stepped aside and let us into the train. You wouldn’t expect such a reaction in a time of war.

We stood in the train which rode quickly to Paris. When we arrived it was like another world. Everything was normal, no trace of war. The weather was beautiful that month of May. People walked the streets and went shopping. We took a taxi to a little cheap hotel, because we had no money, only the clothes we were wearing. Luckily there was a man in Paris who owed my father some money and he paid him. Paris lived normally, pedestrians on the Champs Elysées and in the theaters and cafés. Where was the war? But we couldn’t get any food which was reserved only for the French.

The Germans were still approaching. My mother took the initiative to continue to move on. We went to Bordeaux by train. There were thousands of refugees amongst them many Jews. The non-Jews had mostly returned to their homes as soon as they were captured by the Germans. In Bordeaux we managed to get a visa to Haiti and a transit visa to Spain and Portugal. We left the crowded city of Bordeaux to Arcachon, a small coastal town 40 km west of Bordeaux where we rented an apartment, and stayed there for two weeks.

The Germans occupied more and more of France but it was still quiet here. We bought bathing suits and went to the beach. As the Germans were still approaching it was time for us to go. We arrived by train to Hendaye on the border with Spain where the river Bidassoa forms the border. On the opposite side was the Spanish town of Irun. There were many people and we had to pass through the French customs first. People were looted by the French border officials. All your luggage had to be inspected and they decided which item was allowed in and which was not. My mother gave them a few gold coins and finally we passed through.

We were in Spain and free! We sat down in a little café opposite the station waiting for the train to take us through Spain to Portugal. Suddenly we heard roaring motorcycles on the French side of the bridge, just a hundred meters from us. German soldiers on motorcycles with side-cars were scaring people away, they pulled down the French flag off its pole and replaced it with a Swastika flag. Although we were safe, it made a horrifying impact on us. That was June 22nd, 1940.

In Portugal the family was sent to the university town of Coimbra. We had to renew our visa every two weeks. Because we stayed there for some time, I went to the university library where I could read newspapers from around the world. For the Germans, Dunkirk was a victory where they captured 600,000 prisoners of war, while for the British press 200,000 soldiers were saved there...

The Portuguese were not very happy with all the refugees, nevertheless the population was kind. The family moved to Lisbon and rented a small house. In the US, Henri Stolz’s sister Laura was applying for an immigration visa for us but the American State Department put many obstacles. Time passed by and we ran out of money.

Evaluating the situation, my father remembered the time he spent in the Dutch East Indies and the good life he had there. Being Dutch citizens we could go there without much difficulty. Father visited the Dutch consulate to secure the family’s voyage to the Dutch East Indies which was quickly arranged. But grandmother had only Polish nationality and was not allowed to go along. Therefore I stayed behind with her in Lisbon, while the family left by boat to Java.

Already speaking some Portuguese I obtained a job with a firm that used my language skills. After a few months, the Dutch consulate realized that the old Polish lady was no threat to anyone and so we were allowed to make that journey to join the family in Java. We left in a small freighter ship with twelve passengers from Lisbon around Africa to Java, sailing first to the island of Madeira, then to Boma in the Belgian Congo, then several harbors, and around the cape to Durban in South Africa. In Durban we visited the Gurwith family who were living here and we received some money from them. Via Lourenço Marques in Mozambique and the Seychelles islands we sailed in a sea where German boats were attacking unarmed allied freighters and sank them. No lights were allowed therefore on board the freighter. One night we had to stay awake on deck near the lifeboats. Finally we arrived at Batavia (which later became Jakarta) in Java where we were placed in a camp for a while.

In the meantime my father was back to work again trading in diamonds. He felt at home. We rented a big home in Bandung, a city in the hills. After a while we had no fewer than 22 servants. Everything was fine.

My brother and I were drafted to the Dutch army Reserve Officers Corps. My brother rose to the rank of the camp’s aide. In December 1941 the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor which meant war. Dutch East Indies (Indonesia) was also attacked and eventually occupied by the Japanese. My family was placed in a camp and my brother was put in jail. I was very lucky since because of my fluent English I was sent earlier in an army delegation to India to liaise between the Dutch and the British armies.

By now, the Japanese occupied all of Dutch East Indies so there was nothing for us to do in New Delhi, but I couldn’t go back. I asked the British to give me some military position and in 1942 I received a special permit to enlist in the British army and was transferred from the Dutch army to the British army. I was given the rank of Lieutenant in Force 136 with the mission to make contact with the Karen people, Christians who lived in the jungles of Burma behind the Japanese lines. We had to supply them with arms in their struggle.

I was transferred from Rangoon to the Allied Forces Southeast Asia and was given several assignments in the War Crimes Commission which investigated the Japanese war crimes. In the beginning I had some contacts with my family. Then we left Burma. There were many internal problems in India with Hindustan and Pakistan and also in Malaya. I was in Singapore with the General Staff Office. I learned from my aunt Laura in New York that my family had left for Australia and I renewed the contacts with them. Meanwhile my father was back to work again and I met him in Singapore when he came for business.

At the time I signed up with the British army to serve in the “Emergency Commission” as long as there was an emergency. As war ended I asked for demobilization, but the British saw it differently: Because of the situation in India I had to remain in the army since I was an officer in the British army in India. So I was involved in the hostilities between Muslims and Hindus, between India and Pakistan, a conflict that inflicted tens of thousands of victims and where millions were shifted from one country to another. I had to defend the British interests. I was 24 years of age.

Life in the jungle was hard mostly because of the heat and the fighting. In Singapore I had a very good life, but in India it was a permanent state of alert again. We were being shot at and we fired at the Indian people who were fighting an anti-British struggle for their independence. Finally in 1947 I got a notice that I was being released from army service. I had to be in London in person for the demobilization process. We arrived some 2000 men by boat to England. I was given civilian clothes and a large sum of money because I had not gotten my full salary for years. There were also extras for jungle time, dangers, etc. I was finally free.